Over on Twitter, James Wood tweeted yesterday (@jamesrwoodtheo1):

After Christ and your family, committing to a few key theologians is a profoundly life-giving enterprise.

My studies have been largely framed by Augustine, Calvin, Torrance, and de Lubac. I imagine these figures will always be with me.

I had to pause and think about which theologians I am or would like to be committed to. I scribbled on a Post-It note thinking about who are the people who have framed my own studies. I came sideways into theology as a philologist and historian — which I principally am! Who are the theologians I circle back to, though? They must be there, at one level.

Some, I circle back to in my mind. Others I reread or read more of. I don’t have the Post-It with me, but as I recall contenders were:

- Athanasius

- Augustine of Hippo

- Leo the Great

- Boethius

- Maximus the Confessor

And then I thought — but wait! I spend so much time with ascetics and mystics…

- Cassian

- Evagrius

- Bernard

- Benedict

This leaves out Anselm, though, a man whose work I circle back to in my head and heart quite often. I never got around to even writing down Gregory Palamas.

It was also noteworthy that James listed some 20th-century greats on his list. Am I not influenced by people after St Bernard?? What about my own Anglican tradition?

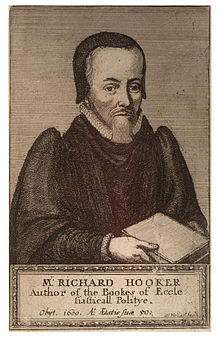

I looked at my calendar and realised that the next day — today — was the commemoration of Richard Hooker. His Learned Discourse of Justification is something that sticks with me. It’s the only piece of modern stuff I have published on, after all! But also, of course, the Prayer Book. The single theological text I have read the most.

So I settled with Hooker but also reflected that there are two lists. Athanasius, Augustine, Leo, Anselm, and increasingly Maximus and Boethius with Hooker on the one hand, and then Cassian, Evagrius, Bernard, Benedict with the BCP on the other. It may seem like a lot of theologians to invest my time in. No doubt they will settle with time. But the one list is the guys I read for theology-as-argument, the others I read for, well, theologia — “If you truly pray, you are a theologian.” Not that the two categories are hard and fast, as any reader of them knows.

Before pondering, “Why these?” you may ask: Why the experiment?

I think James is right in this. It’s an idea a friend once floated at Davenant as well. Devote yourself to a few whom you will read deeply and repeatedly. Get to know them as friends and companions. See their various facets from multiple angles. Love them. Engage with their ideas. Disagree with them.

Doing this will train your intellect and hopefully also your delights and loves. It will help you focus your mind as well. There is so much out there to read and know, coming back to one person and finding his resonances and particular themes and shades and variations and transformations helps train the mind beyond the chaos that our modern social media age creates.

It also teaches us to read deeply, and to reread deeply. My most-read explicitly spiritual books (so not Homer, Virgil, or The Lord of the Rings) are the Confessions of St Augustine, On the Incarnation by St Athanasius, the Life of St Antony approved by St Athanasius, The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius, the letters of Pope St Leo the Great, and the Rule of St Benedict. I go back to them over and over. There is something new every time. Or things I’ve forgotten. This is why these authors. I choose these specific books as companions because they delight me.

I am also exploring the vast, spreading corpus of Augustine, including multiple readings of De Doctrina Christiana, The City of God, and hopefully soon De Trinitate. I would not have wanted Augustine on my list of contenders 10 years ago. But I’ve had to grapple with him because of his importance and because teaching him is, I believe, important. And I’ve come to love the Bishop of Hippo.

The wider Athanasian corpus I also delved into for the “historical theology” and anti-Arian stuff but found much more hiding there about the doctrine of God and the Trinity than a standard, pop-level church history book could ever give a whiff of.

Why Leo? Good golly. I have sat with the medieval manuscripts of the letters. I have probably read his famous Tome more times than any other piece of ancient theological writing! That’s “Why Leo?”! I also appreciate his ability to synthesize, not to mention his evident rhetorical skill.

The newcomer Maximus is burned into my mind because he came to me like an electric strike of lightning and set me on fire. As you may know, my original patristic loves were the monks (hence Cassian, Evagrius, Benedict, Bernard). And then I began working away at Christology, greatly enjoying the work of Cyril of Alexandria, Severus of Antioch, and others. When I met Maximus, it was both of these worlds colliding at once. The ascetic and the mystical wedded strongly to what we today call theology, explicating the beauty of the hypostatic union and Chalcedonian Christology, all within a trajectory clearly set by Athanasian Triadology! The blossoming of the legacy of both Athanasius and Evagrius.

Finally, though: Hooker and the BCP. I’m not sure if Hooker will be my long-term Anglican companion. But I’d like to find one. I am Anglican, after all. I pray with the Prayer Book. I sing Anglican hymns. I read Herbert and Donne. I listen to Purcell and Orlando Gibbons. And I once upon a time proposed the idea of an Anglo-Patristic Synthesis! But I think Lancelot Andrewes might end up being my Anglican theologian. Maybe Jeremy Taylor? We’ll see.

This doesn’t mean I won’t read others. Of course not! But these will probably be my mainstays, even as I go further with the Cappadocian Fathers or St Ephrem the Syrian or the scholastics or Palamas.

Who are your theological companions?