The other day, a Baptist on Twitter said he had a friend looking at Eastern Orthodoxy and was looking for recommendations. I recommended Kallistos Ware’s two book The Orthodox Church and The Orthodox Way, plus Andrew Louth, Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology, and then, after that, The Way of a Pilgrim and some time looking at the Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom.

Another Baptist jumped in asking why I was only recommending pro-Orthodox books. My response was that I read them without converting, so I’m totally comfortable recommending them to others. I also admitted that I’ve never read a single anti-Orthodox book. Anti-Orthodox books are probably like those anti-Catholic tracts or the chapter on Roman Catholicism from Fast Facts on False Faiths — inaccurate, easily taken down by the informed Orthodox/Catholic, and sowing dissent amongst fellow believers. Just a hunch.

I also said that I have not been converted to Eastern Orthodoxy in part because I know the western tradition. I know the BCP and the Articles. I am rooted in Anglicanism such that I know what my own church (officially) teaches on a lot of disputed points.

When I first started getting to know Orthodoxy, I lived in Cyprus and was only 22. But even then I had with me my trusty 1962 BCP (a gift from Grandad on my confirmation!), and when I read a book that claimed to be “What Every Protestant Should Know about Eastern Orthodoxy”, I found myself not fitting the beliefs the author (a former Southern Baptist) touted out as “Protestant”, whether he was discussing sacraments or the Bible or the atonement. I would double check my BCP and the Articles and say, “Well, Anglicans don’t believe that!”

So this is the first point of tonight’s meditation. If ever asked why I’m not Orthodox (which would probably happen someday, given the presence of icons in my life, a komboskini in my pocket, and a few other hints), my answer would now shift from before. Before — I think I blogged about it here once — I would list things about Orthodoxy with which I disagree, most especially the fact that they claim to be the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church (and no one else to be).

But now, if asked, the answer is because I am convinced of the truths of Anglicanism. It is the same reason, mutatis mutandis, that I am not a Baptist, frankly. For example, one of my favourite personal quotations from a conversation long ago, and a belief I still hold, is, “I am a follower of Richard Hooker.” I embrace his articulation of the doctrine of justification by faith alone — which is not the same as the caricatures produced by many of this doctrine’s opponents and which I believe is a natural following through of the teachings of St Augustine of Hippo.

To choose a second example, I also believe in the historic articulation of the Articles that Holy Scripture contains everything necessary for salvation — but, as an Anglican, I also believe in the place of the Church’s tradition as the interpreter of Scripture as well as the provider of things that are not, strictly speaking, necessary for salvation, yet nevertheless good for us and not be set aside lightly. For example, the Book of Common Prayer! Singing the Te Deum! Facing East at prayer! Anselm on the Atonement! Thomas Aquinas on the doctrine of God! All these things are available to the Anglican, but they are not, so far as I understand it, necessary for salvation (re Anselm and Thomas, I mean in terms of the very specifics of their teaching).

Over my many years of being Anglican and praying with the BCP and learning about my English spiritual heritage, simultaneously going into the Fathers but also the monastic fathers, medieval theologians, and the Eastern Orthodox tradition, I have become rooted in seeing the BCP as a rule of life, as an ascetic system that also provides us with so much positive truth (as I blog here often).

Part of why I have become rooted in this way is precisely that dance with Eastern Orthodoxy that I began almost 19 years ago. I have had my times when I seriously considered converting, sitting with Andrew Louth in his study, drinking coffee out of Beatrix Potter mugs, or being taught about icons by Fr Ioannis, being shown how to do prostrations by Fr Raphael and being given his teaching on the Jesus Prayer.

One of the things that often bothers me when people convert from one church to another is that they don’t always seem to know what they’ve left behind. As a lifelong Anglican of a Levitical family, I made it a point to learn what Anglicanism — both in its particularities but also an expression of western, catholic Christianity — actually teaches and has taught.

One result of this is a very different response to John Zizioulas, Being As Communion, from that of the former Southern Baptist I mentioned above. He read Zizioulas and his mind was blown. “We have nothing like this in Protestantism!” I read Zizioulas, and I loved it, and I saw how the teaching on the Trinity in that book was compatible with my comfortable, disturbing Anglican heritage. Why leave?

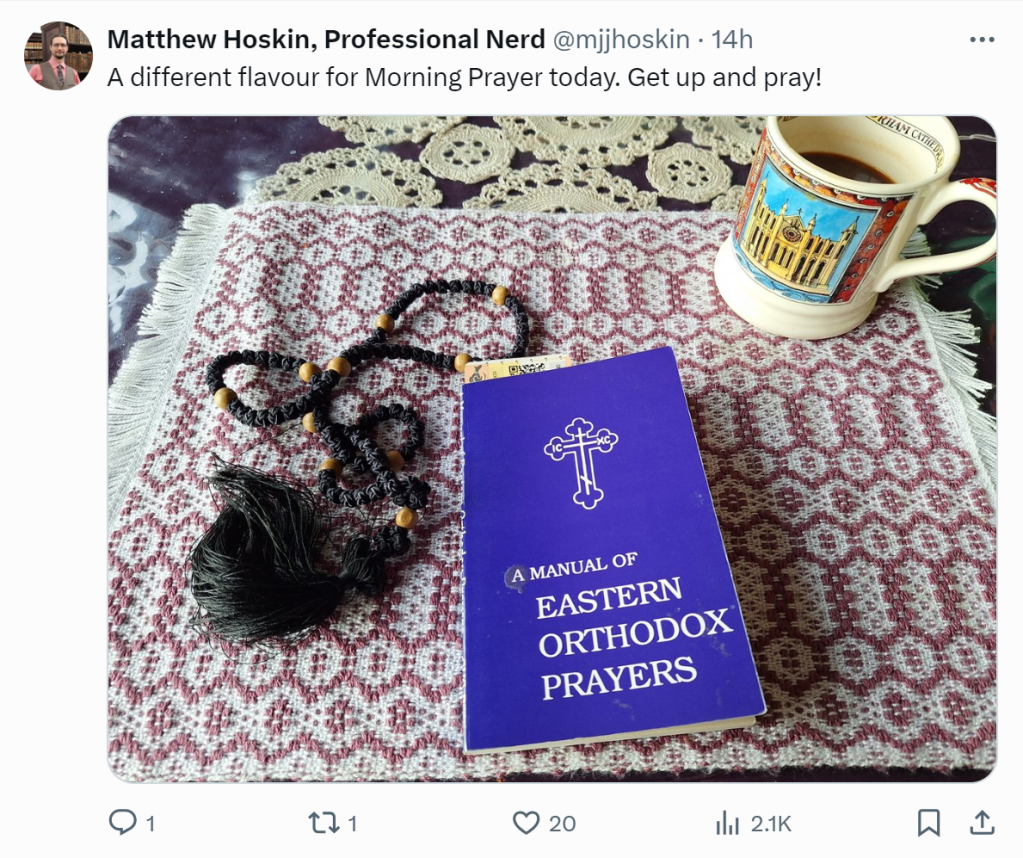

I and many other Anglicans have benefitted so much from our engagement with Orthodoxy, our friendship with Orthodox Christians, our attendance at Orthodox services, our conversations with Orthodox clerics, and our reading of Orthodox books. As a result, I can post things like this without feeling like I’m betraying my Anglican heritage:

Posting that, amusingly, got me accused of superstition. Apparently, I am supposed to burn my Manual of Eastern Orthodox Prayers. Right.

But positioned within Anglicanism, I see no reason why I should not pray the prayers in that book that are beautiful expressions of orthodox faith common to all Christians. Nor why I should not use a komboskini for the Jesus Prayer. It is much easier to pray the Prayer with one than without.

To close, because I have had positive experiences with the Eastern Orthodox Church, I do hope other Anglicans encounter them and see what we have in common and what they have to offer us, especially in how they treat the Fathers as living voices for today (something classic Anglicans used to do as well!) and in the practice of the Jesus Prayer, combined with the wider Eastern hesychastic tradition.

Such encounters, I believe, will help us grow deeper in our union with Christ (itself a strong Puritan theme…). Perhaps we can see revival in our churches as a result of an Anglican hesychastic movement!