If you were to check the definition for the Latin adjective spiritalis at the wonderful website logeion.uchicago.edu, you would learn that, according to Lewis & Short (one of the standard Latin-English dictionaries out there), it means:

Of or belonging to spirit, spiritual (eccl. Lat.): substantiae quaedam, Tert. Apol. 22: bellum, id. adv. Marc. 4, 20: si spiritali lacte pectus irriges, Prud. στεφ. 10, 13; Vulg. Gal. 6, 1; id. 1 Cor. 15, 44.—Hence, adv.: spīrĭtālĭter (spīrĭtŭāl-), spiritually: caro spiritaliter mundatur, Tert. Paptism. 4 fin., Vulg. 1 Cor. 2, 14; id. Apoc. 11, 8. (This is definition II)

On the same website, the Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources (DMLBS, an exciting and relatively recently completed project) gives much the same fare but with a wider range of meanings simply because of the many ecclesiastical and theological documents to come out of medieval Britain. The word spiritualis just redirects the reader to spiritalis.

This is, quite simply, expected. Certainly I wouldn’t imagine finding a different definition for the most part.

However, the introduction to the Cistercian Press translation of St Aelred of Rievaulx’s Spiritual Friendship takes us to new semantic worlds. In Cistercian orthography, spiritualis with a U refers to spiritual in terms of relating to the Holy Spirit, and spiritalis without the U refers to spiritual in all those other ways listed in Lewis & Short and the DMLBS.

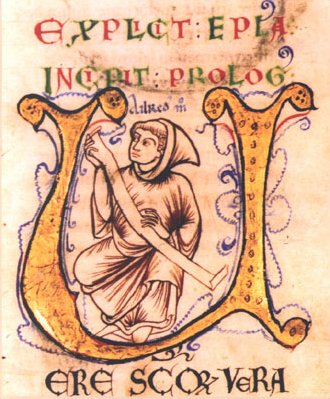

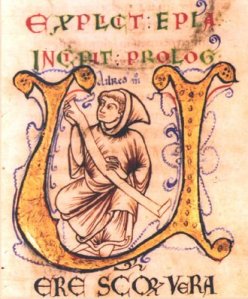

This distinction has stuck with me as an interesting way of looking at things — and I would be interested to compare Cistercian and non-Cistercian copies of the Church Fathers to see how they render spirit(u)alis in different instances, because the difference in orthography can signal how the monk copying the text interpreted it as he read it. If I had time I could do this, starting with Leo the Great because I know where to look at some of the Cistercian copies of his letters. Well, frankly, I know where all the manuscripts of his letters are. So he could be an interesting test case — but it could come to nothing, in the end.

Anyway, all of this popped into my head the other night as I started my summer reading, a reprint of the 1904 edition (ed. Pohl) of De Imitatione Christi by St Thomas a Kempis. Here you will see on the title page that the work is actually titled Admonitiones ad Spiritualem Vitam Vtiles — Exhortations Useful for the Spiritual Life.

Now, this St Thomas was not a Cistercian (rather a canon regular of the Order of St Augustine), but he is enough after the Cisterican world has been born, enough into the age of Cistercian mysticism having done the rounds, that a contemplative such as he (as he certainly was, easily noted in the Life I translated for Greg Peters’ Cascade Companion to Thomas a Kempis) would have had access to the Cistercian spiritual tradition.

And so it strikes me that the “spiritual life” referenced here in the title may not simply be the life of the human spirit, but, in fact, the life of the Holy Spirit animating and invigorating the human spirit. This is, after all, what St Paul means for a spiritual or pneumatikos human to be. Someone enlivened by the Holy Spirit of God who is seeking the things of God and no longer living according to the merely natural world as we experience it.

This is just a hypothesis — and the material of the hypothesis regarding the content of the Imitation may be true even without the Cistercian connection. Either way, I hope it can help you think through the things you meet in the world.